November 26, 2014

By J.I. Abbot

Many members of the Tunxis faculty and staff grew up in libraries…some of us more or less literally. For my part, I remember being about nine and scoring a first edition of a little-known sequel by author J. M. Barrie to Peter Pan with my dad in a fantastical secret room of the New Milford Public Library. This particular volume, from the beginning of the 20th century, had never been read; it came from a time when many books had sewn-in “signatures” or sections that needed to be cut one by one by the reader—sort of like cracking pistachio shells for a snack. These specific pages were uncut. Until we got to them.

Just the mysterious existence of that room…and a book not even one family member or friend knew existed…and a test drive of what was to become my first pocket knife—the whole experience was a bona fide adventure associated with a library. Later, serving in Bloomfield’s Prosser Library’s PIBOR (“Prosser Important Board of Review”) club under a true mentor, Mary Etter (now director of South Windsor Public Library), gave a future professor the life-and-career shaping notion that I got to have an opinion—particularly about any book in my immediate vicinity.

When I started teaching at Tunxis full-time in 2006, a collaboration between fellow book adventurer Rachel Hyland and me was inevitable. To give you just a sense of her talent, Rachel has been honored by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the New York Times, chosen two years ago from contestants across the country as one of the most innovative librarians in America. But notwithstanding such impressive laurels, she is one of the most down-to-earth people you’ll ever meet. In 2013, after talking with Rachel, I began to cement an earlier suspicion—first instigated by master New Media and literature teacher Prof. Steve Ersinghaus—that my lifelong love of comic books and graphic novels had some kind of connection to the smartphone culture and new media-savvy world of many of our Tunxis students.

Steve had got me started on the idea that new media culture was itself collectively reinventing the ways we can think about narrative in the classroom. An Instagram- or Twitter-based combination of image and soundbite might be akin to a panel in a graphic novel or a particularly elegant and concise infographic. Linear was “out,” or at least no longer obligatory—but students still needed clear roadmaps to navigate through nonlinear weavings. Understanding word and image as meaningful bits in an infinite mosaic—sort of a new Imagism for the era of social media—began to influence how I taught. A tweet or text message also began to look suspiciously like a Lego building block—it might be possible to construct a whole world with the right “master builder set.” This was when Rachel put The Philosophy Book in my hands. I think it was at least in part in response to my very text-heavy / visually crappy slide shows that the remedy was diplomatically offered.

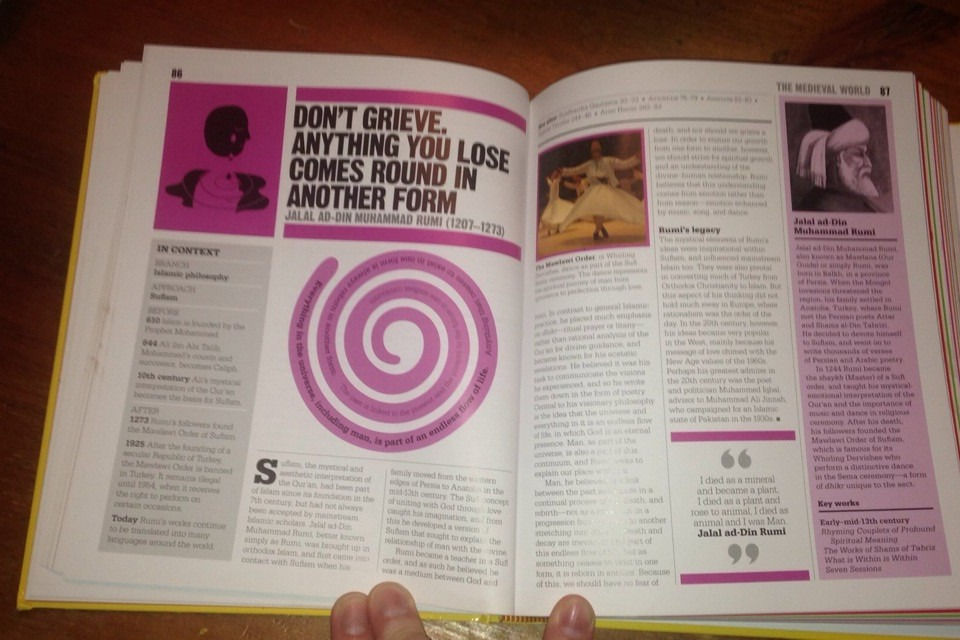

The book was like a graphic novel’s response to the discipline of philosophy. But it’s part of a whole series—”Big Ideas, Simply Explained”—published by the Dorling Kindersley (DK) imprint of Penguin Books. The Politics Book, The Economics Book, The Psychology Book, The Religions Book, The Science Book, The Business Book. . .each of these is a thing. My wife and daughter and I have long been in love with the broader “culture” that connects many DK titles—the standard of a “user interface” of impressive and rich graphics and overall design elegance that steers the relationship between text and images in a way that is easy on the eye overall without skimping on content. This year, IKEA Corporation famously reminded us that a beautifully designed book or printed volume is the most classic example of a good user interface or UI.

On any given two-page spread of The Philosophy Book, for example, readers are treated to minimalistic but potent stick figure images, welcoming headline-style typefaces, at-a-glance sidebars titled “In Context” that give concise but highly useful data that situates a thinker or movement within the patterns and disarray of history: what came before; what after; who the key players, personnages, friends, and foes are—and yeah, also little gems: quotes to hang your hat on and snap the personality behind the ideas into focus.

Anyone who knows me at all is aware that I‘m conflicted about the allure of digital technology, as I’ve had my run-ins with the ugly side of that world. But further, I’m often rather old school with respect to the sheer mass of my classroom media: students in my classes for two decades have had to deal with what my friend Dr. Marcia Seabury, Chair of English at Hillyer College, University of Hartford, dubs the “cinder blocks” also known as 2000+ page anthologies. I still tend to think that there’s a certain initiatory element to students handling such book-bricks: part of the rite of passage called “being in college.” But I found last fall that the design savvy of the “Big Ideas” series is a helpful complement to (or, in a pinch, even respite from) the primacy of lengthy texts. I’ve advised students to curl up in a corner with The Philosophy Book—and, the following term, with The Religions Book as well—when either I or the cinder block book was giving them philosopher’s block or a headache.

To close for now, I just want to tell you what Rachel and I are doing with this column. The real-space-and-time Tunxis Library now has a display—just as you come in: “HiA’s Finger is on…The PULSE”—that lets you test drive whatever books we are jointly featuring, reviewing, or even perhaps slamming on the HiA blog (www.hia-tunxis.com) and Library blog (tunxislibrary.com). Send us suggestions; let us know of any books you’d like to see featured. We hope this book community can grow, and invite you to help us grow it! Happy Thanksgiving to you all.

Display photo by Rachel Hyland.

Comments